home » news » buildings and authorities » New Zealand » Wellington

Shifting sands at Oriental Bay

In the past 100 years the “rotunda” at Wellington’s Oriental Bay has been buffeted not just by wild seas, but also the less predictable winds of change. Shifting needs, mores, and economies have seen the structure reinvented several times, and it’s about to happen all over again.

Oriental Bay is a special little spot in Wellington, just along from the central business district. It’s the only bathing beach in the inner city and on a fine day it’s postcard material. Photos are usually taken from either end of the beach, facing the “rotunda”.

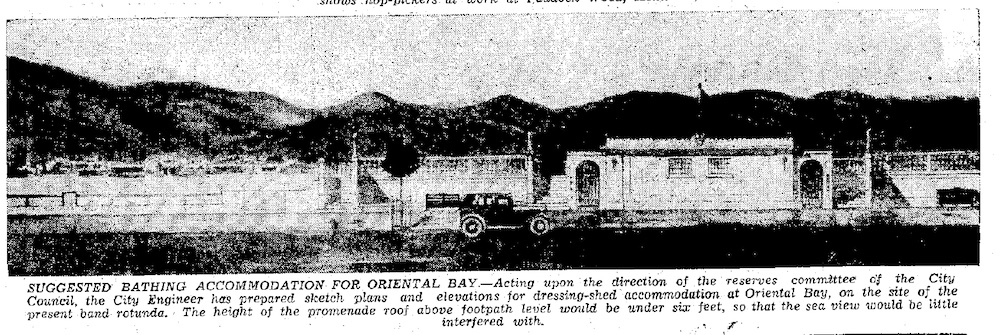

Rotunda is a misnomer now, but easier to say than “projecting semicircular embankment”. This projection was built in about 1918 on a rocky outcrop, with costs kept down by using street sweepings (otherwise known as horse manure) as fill. Its perimeter sea wall was cleverly designed to shield against rough seas and provide a comfortable spot to sit when the weather was fine. The real purpose of the projection was to house a second hand band rotunda hauled in from Jervois Quay. Calls to site a captured enemy gun battery next to the rotunda as a war memorial were thankfully resisted.

The new band rotunda and its surrounds proved very popular with the crowds, but within a decade the timber band rotunda had fallen into a state of disrepair, the council having neglected to maintain it.

The dilapidation, coupled with other factors, led to calls for the rotunda’s removal in the Thirties. Local residents were growing alarmed at the congregations of “brainless young hooligans” pulling up plants and rocks around the rotunda, and howling their “ragtime songs accompanied by an amateur ukelele player.”

The dwindling crowds attending the official band performances had to strain to hear the music above the din of the motorcars hurtling past. The performances themselves became few and far between as bands moved into theatres and broadcasting studios, and stopped receiving council grants. In 1936 the now dirty old rotunda was carted off to Central Park to be tarted up for its third incarnation.

On the rocky beach adjacent, the surging numbers of bathers were finding it difficult to comply with strict by-laws governing their costumes. It was illegal to change on or around the beach, but without alternatives people did so anyway. One man brought the issue to a scandalous head by depositing all his clothes on the beach and taking a swim in the nude .

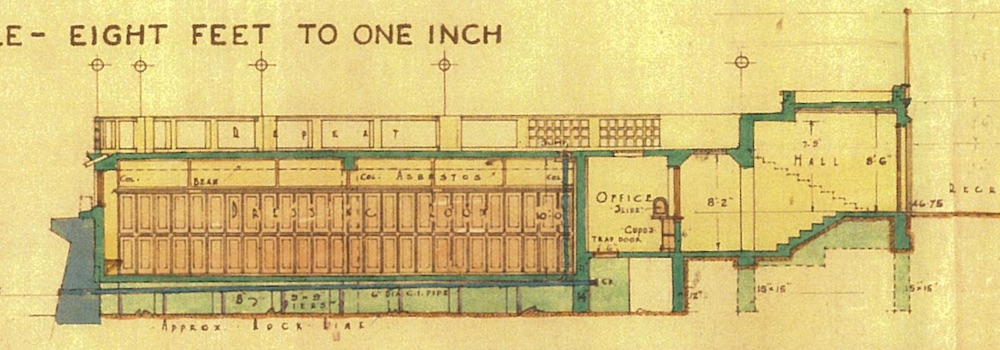

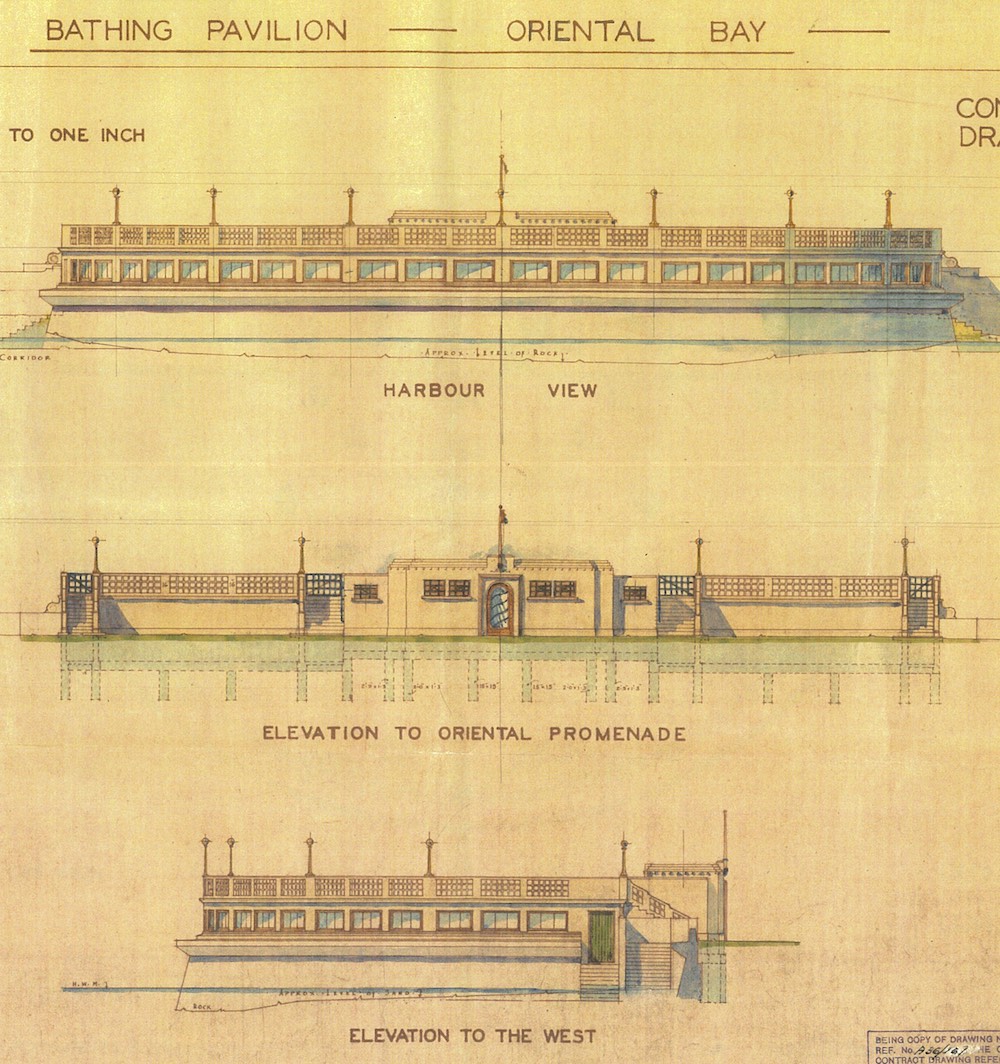

In order to maintain common decency in Oriental Bay, the old dung fill was removed from the projecting embankment and asbestos-lined changing rooms were built within the original foundation wall. The new pavilion was designed by the City Engineers Department in ablutional moderne. A highlight is the arched glazed door, added late in the design. The building was opened with bands and fireworks on May 1st, 1937, long after the end of the bathing season.

The city corporation was compelled to announce that beach access would still be open to people not willing to pay 10s 6d a season to use the new changing rooms. Long-suffering residents continued to be treated to the view of penny-pinching citizens donning their togs on the adjacent reserve, meanwhile bathers were complaining that the rooms closed at 4pm, before the summer afternoon peak.

As beaches go, Oriental Bay was rather a skinny and stony sliver in the Thirties. This was remedied during the war, with 15,000 odd tonnes of sand brought in as ballast from Bristol and dumped on the foreshore. This process happens every decade or so when people notice that all the sand has disappeared. The bathing pavilion did its bit for the war too, being fitted out as a gas decontamination chamber, should the need have arisen.

The threat to common decency of changing in public lessened over the following decades. Beach movies, surf music, bikinis and Coppertone all did their bit. By the mid Seventies bands rarely appeared. The changing rooms were underattended by bathers, and overattended by others. A writer in Home and Building in the mid-Eighties reminisced about, “a whole semi-circle of changing rooms and loos below ground level, hung over with gloom and disrepair which gave sport to peeping toms and other city loiterers.”

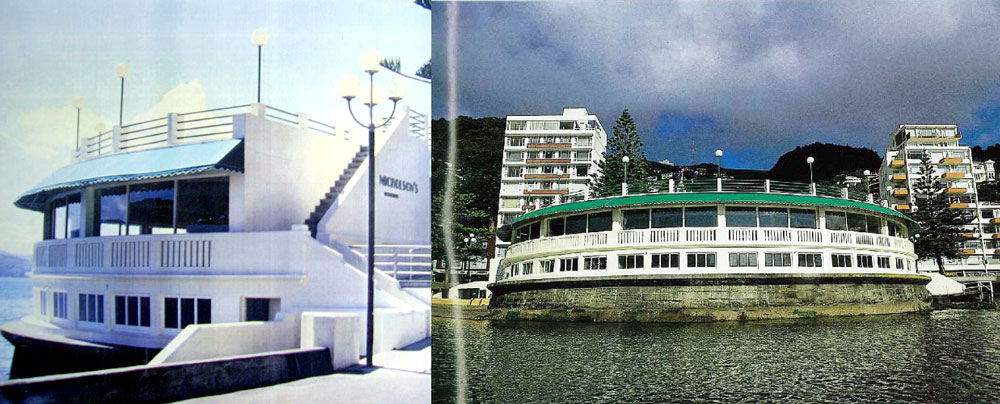

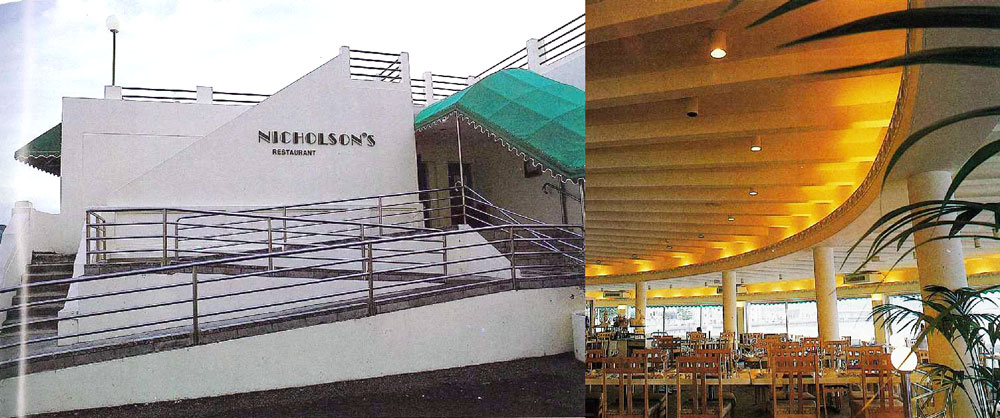

Facing remedial work on a structure they didn’t want or know what to do with, Sir Michael Fowler’s pro-development council lifted the rotunda’s open space designation and leased it (complete with rooms below) to emigré restaurateur Harry Seresin’s Settlement company. Grahame Anderson of Ampersand Architects designed a restaurant to replace the open platform. According to heritage reports, Hunt, Comeskey and Scott were also involved. The design may have been stymied by a category 2 heritage listing in late 1982. Whatever the reason, Seresin’s scheme was eventually shelved.

Into the breach stepped developer and restaurateur Peter Andrews. He engaged Chris Johns of Auckland architecture practice Sinclair Johns to rework the earlier design ( Chris Johns is my late father ). The constraints were many.

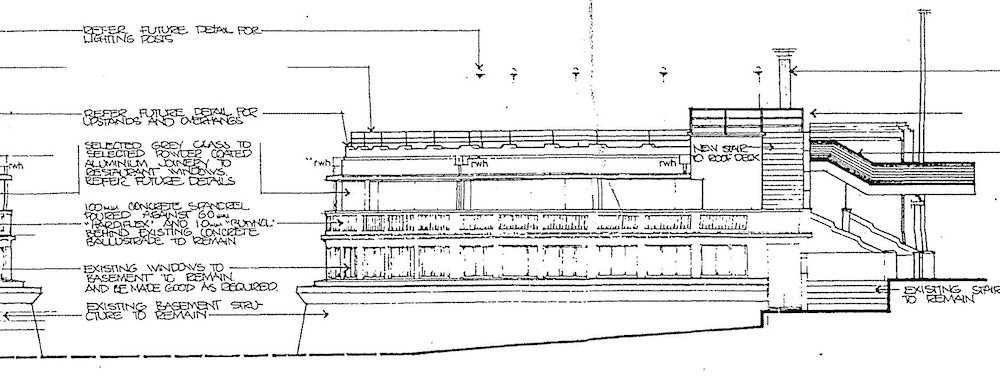

To respect the structure’s new heritage listing, the style said Johns, had to be, “in sympathy with the original 1933 building, neither stating the present nor forgetting the past.” So the restaurant sat behind the 1930s concrete balustrade, the viewing deck was reinstated above, and the tired changing rooms below were refurbished for community use and a kitchen.

To pacify the locals, the overall height was lowered from the earlier design and opening hours were reduced. To comply with accessibility laws, a maze of ramps was introduced at the entry. Though I’m biased, it’s a tick for Sinclair Johns that this layer cake ended up looking and working as well as it did. The NZIA gave Nicholson’s restaurant a commendation in 1985.

In the mid-Nineties, with the restaurant under new management, architects Hunt Davies were called in to design a cantilevered concrete balcony around the perimeter. A shiny red plastic canopy was popped on at around the same time, signalling the change inside – from posh to cheap ‘n’ cheerful. Thanks to a biting recession, a resurgent café culture, and new Asian alternatives, high end restaurants were doing it tough.

By the late 1990s the sand had disappeared (once again) and the beach and rotunda were looking unloved. Oriental Parade’s unreinforced and undermined concrete sea wall required urgent work (the need having first been identified in 1939). It was decided that the bay would be “enhanced”. In preparation, a heritage report for the rotunda and sea wall was written by conservator Ian Bowman.

Bowman thought that the ramps and entrance canopy altered the original symmetry for the worse, taking focus away from the old entry door. The old rooms downstairs were deemed to have heritage significance while the restaurant additions had none. Nonetheless, he didn’t recommend demolishing the structure back to the 1930s. Instead, he suggested replacing the balustrading with something a little more ’30s than ’80s, scaling back the balcony and canopies, and adopting a less glaring palette. He also recommended some serious maintenance, as even then the building was in trouble.

Little if any of the report’s proposals were taken up by council. Some new toilets were fitted into old store rooms, and a pedestrian access way was wrapped around the base of the rotunda’s sea wall. The rest of the building was allowed to slip further into decrepitude.

Structural concerns about the old slab above the changing rooms led to four core samples being taken in 2010. It was several years till the results were reported to council. The 7” slab, which was once the roof deck, had cancer and was ageing fast. While suitable for restaurant live loads, it only had another five years left in it.

The engineers advised in their report that remediation needn’t be expensive and could be done in a staged way during future refurbishments. But who would pay for these necessary refurbishments? In 2012 the annual funding for the community rooms dried up, though the closure was pinned on leaks and the need for earthquake strengthening . Funds have been allotted to earthquake strengthening the building in most budgets since 2012, but little if any have been spent. Presumably the council has been collecting rent for the last 30 years, but it isn’t clear from their annual reports how much this might have been or where it went.

Update 26/11/19: The council has recently published a new page on their website stating that the rotunda was earthquake strengthened in mid 2015. Commenting on the condition prior to remediation: “The building has a reinforced concrete slab floor and walls and much of it is pretty solid.Only the inter-tenancy floor requires work.”

The Bluewater restaurant owners surrendered their lease early in 2016, several years ahead of schedule. Later in the year, the city felt the effects of the Kaikoura earthquake. In the aftermath the council had to deal with hundreds of yellow and red-stickered buildings. The rotunda slipped down its list of priorities.

Councillors were quite open with their thoughts. The building was in a poor state, would cost millions to fix, and would only be around for a short time due to sea level rises. They did not have money lying around to spend on it. Councillor Young appeared to blame the building for its state of neglect. “It could be wonderful; it’s currently an eyesore and liability. Oriental Bay deserves better.”

In May last year the council called for registrations of interest for the commercial redevelopment of the rotunda, then proceeded to down-sell the project. It admitted that the prospects for the building were limited and they needed someone to take it off their hands or they might have to “take it away”. It was 1981 all over again.

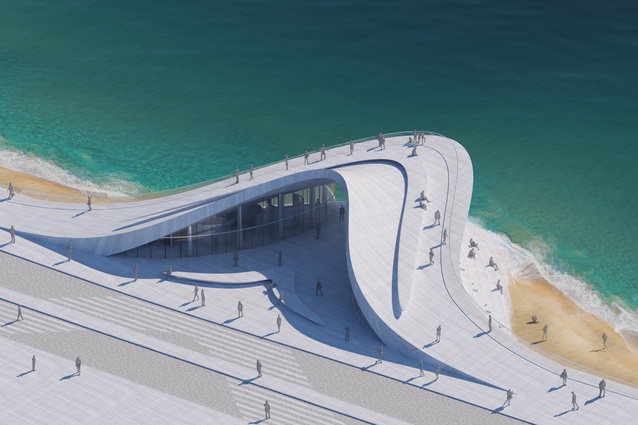

Perhaps fearing a mediocre result, a group of academics at Victoria University organised a concurrent architectural ideas competition restricted to young architects and students. More than 200 entries arrived from around the world, with the top three places going to architects from Russia, Denmark and Argentina. The results are scattered around the web, but you’ll find thirty of them at the ADEDU Facebook page.

“Although it is only an ideas competition, it could leave a positive impact on the future development of the site.” A hopeful ADEDU competition jury.

“You have to start with dreams. I think the designs are very inspiring. But every good design needs money, of course. We’ve got a liability which is potentially an asset. But I think never waste a good idea. I’ll make sure staff see this and make sure we respond.” Cr. Iona Pannett, November 2019

But by the time of Pannett’s remarks, the real sketch design had been completed. Since last year the council has been working with noted heritage developer Maurice Clark. Renderings dated November 2018 were released to the public this May, following several in-camera council meetings through the early part of the year. The council gave the scheme its blessing and found 300k for a contribution.

With veteran engineer and developer Maurice Clark at the helm, all should be well. The media was upbeat, saying he was the right man for the job, given his record in taking on tricky projects like the Public Trust Office restoration. His obvious passion for unique old buildings is an improvement on the council’s apparent take on the rotunda as a headache which recurs every 40 years or so.

At the moment, the rotunda adopts a pose that is low-slung, white-washed – seaside moderne if you like. In the new renderings, it becomes a dun-coloured drum, bound with tall windows. I’m not sure what it’s trying to be, if it’s even trying to be anything. There’s no sign of an Oriental Parade elevation, nor a designer’s name. I’ve found nothing to say whether this design is early days, or developed. I hope it’s the former, as it needs a lot of work.

Clark sees one of the major problems with the existing restaurant being its detachment from Oriental Parade, due to the level change and access ramps. We are in the age of activated street fronts I suppose. In the renderings put forward, the floor level of the main room would be lowered to match the footpath outside. In a radio interview Clark envisages the new space becoming a “banquet hall or stately hall that can be used for a variety of functions.”

Function centres are by nature closed most of the time, and not needing to attract customers off the street, so I’d question the need to drop everything down to street level. Doing this also spells the end of the lower floor rooms and windows, and so the bulk of the heirtage-registered split-level 1937 pavilion, except for the street frontage.

To be lowering the floor level of the main tenancy by six feet is also startling given the WCC’s concerns with projected sea level rises.

In a report released in August, New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) said with, “near certainty that the sea will rise 20-30 cm by 2040. By the end of the century, depending on whether global greenhouse gas emissions are reduced, it could rise by between 0.5 to 1.1 m.” The Wellington City Council has just ditched earlier projections of a 0.6m rise by 2100 for a 1.5m rise, which will see much of the inner city under water.

Clark is focusing on the short term problem – wave action. The design incorporates wave deflectors that could become a future balcony. Looking further into the future he asks, “who knows if the structure will survive a hundred years, in terms of flood inundation? It probably will. It’s worth doing it for even half that length of time.”

Wouldn’t it be better though, to design for the problematic long term, rather than handballing yet another problem to the ratepayers and councillors of 2059?

Posted by Peter on 09.11.19 in buildings and authorities

comment

Commenting is closed for this article.