home » news » heritage

Happy 100 Art Deco, or maybe not

The Art deco style turns 100 this month. Sort of. But what was it then, what is it now, and how did it become associated with architecture?

The term “art deco” is much beloved of real estate agents, though this might be because so many people are searching for it.

“Searches for “retro” Melbourne residences rose 95 per cent, while “Art Deco” was the most popular term out of the 10 most searched ‘period’ keywords over the past year.” News, 20221

If you run a keyword search at your favourite image search engine or monolithic real estate portal, the confusion quickly becomes apparent. You might find federation, moderne, mid century modern houses, fibro shacks, and new homes. The term is being rendered as meaningless as “retro”. Part of the problem is that it was never clearly defined in the first place. It became a style in retrospect, without supporting documentation.

“Art deco” is accepted to be an abbreviation derived from the “Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes”, which opened in Paris in April 1925. The expo was mammoth and had been delayed fifteen years2 by the inconveniences of a world war and the influenza pandemic. Aside from controversial contributions from Le Corbusier and Melnikov, most of the temporary pavilions tended towards the romantic and exotic, appropriating styles from anywhere but Europe.

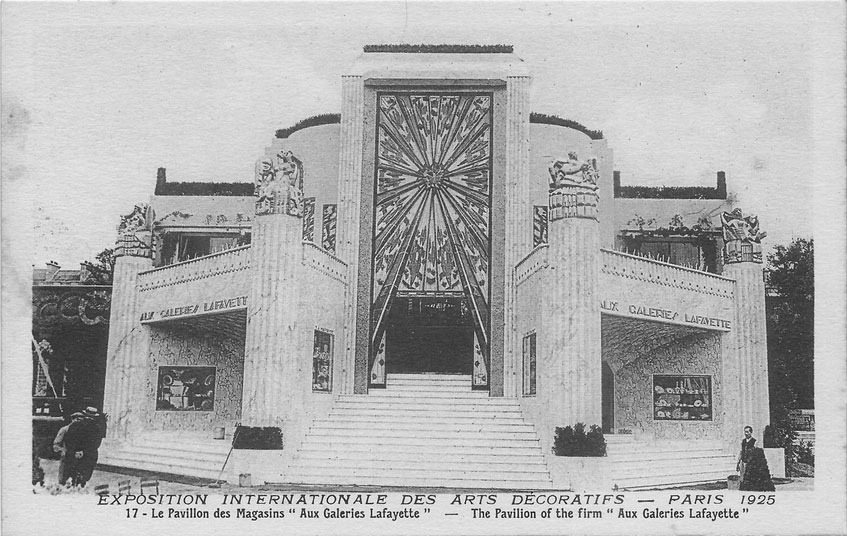

Galaries Lafayette pavilion, 1925. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Only some of the French retail pavilions would be read as “art deco” today – the term was better applied to the content of the pavilions. Hiriart, Tribout, and Beau’s competition-winning pavilion for Galeries Lafayette’s La Maîtrise pavilion brought together sunbursts and ziggurats into a recognisably “deco” exterior. Hiriart and co. designed the outside of the luxury retail box like an oversized inkwell.

The original deriver of the term “arts déco” was probably Le Corbusier, but he was abbreviating it to diminish it. Five years earlier he cowrote Le Purisme, a manifesto favouring simplicity over Cubism’s fragmentation. This was just before he dropped his flowery birth name, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. Though he exhibited at the expo, Le Corbusier was unimpressed with the opulence and ostentation on show around him.

“Our pavilion … will be architecture and not decorative art; it will even have, thanks to this strict intention, an anti-decorative art attitude.3

He rattled off an essay entitled “1925 EXPO. ARTS. DÉCO.”, in L’Espirit Nouveau, mocking the “arts déco”, writing off the discipline rather than any particular style. In short, frivolous hand-crafted ornamentation was still a wasteful crime, particularly when there was a post-war housing crisis.3 “Modern decoration has no decoration”.

Fast forward 41 years. The term “art deco” was resurrected the year after Le Corbusier’s death by drowning. Perhaps it was safe now. It appeared in 1966, in the French retrospective exhibition “Les anneés ’25”. From the fragments of its catalog that I’ve read, this exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs covered the gamut of mid-Twenties decorative arts but rarely strayed into architecture, a model of Gerrit Rietveld’s Schröder house (1924) being an exception.

The late Sixties saw a surge in interest in the fashions and decorative arts from the period. “Art Deco” snapped into place as the term describing the interwar period. Period, type and style had rolled into one. Of course it had to be explained to readers.

“Add Art Deco in your home furnishings vocabulary, if you haven’t already done so. The term, from the French words art decoratif, refers to the modern decorative style of the 1920s and ’30s.” Newsday 26.10.714

Newsday noted that Art Deco meant different things to the two museums who’d quickly dusted off old items from their stores. Brooklyn Museum’s new Art Deco room was chock full of items that were “straight-lined, sitting squat on floor” whereas the Met “pieces are delicately proportioned, gently curved and clearly related to both the immediately preceding Art Nouveau style as well as earlier French designs.”4

Both museums were exhibiting expensive works with high levels of craftsmanship from the 1920s, omitting the Thirties. For the Newsday writer, design fell away after the Great Depression thanks to the “commercialisation and vulgarisation of the streamlining process”.

Preceding the exhibitions at the Met and at Brooklyn, an influential “Art Deco” exhibition was held at the Finch College Museum (1970).5 The New York Times reviewer marvelled at the influences in the 600 pieces on display, which when assembled somehow pulled together into a coherent style.

- Traditional Egyptian, North and South American Indian (especially Aztec) motifs.

- Regency themes.

- Cubism and other modern art forms (specifically the works of Kandinsky, Mondrian, Matisse and Picasso).

- Technological innovations.

- Frivolity and romance

Maybe it’s easier to see the commonalities than the differences when looking back at a decade.

Robert Pincus-Witten at Artforum hoped that the Finch would propell a necessary discussion, now that the style was moving into mainstream popularity and out of the hands of those “attracted by pure camp, kitsch and faddishness” – probably a reference to the many items provided to the exhibition by “style of 1925” fanatic Andy Warhol.

The exhibition was important in firming the definition of “Art Deco” for a modern American audience and cast its net widely, in ways that might raise eyebrows today. Included were chairs and lamps designed by Eliel Saarinen, Gerrit Rietveld, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. The reviewer criticised the exhibition for omitting consideration of the innovations of the Bauhaus school.

Architecture too please

Absent in all these exhibitions was an examination of architecture, presumably as “Art Deco” was still being read literally, and architecture was not thought to be a decorative art. It took the Finch four years to reconsider, then hold a dedicated exhibition “American Art Deco Architecture”. In The New York Times Paul Goldberger commented that it set “such broad limits for art deco that definition becomes almost impossible”, questioning the inclusion of the Hoover Dam and Golden Gate bridge.6

Elayne H. Varian’s architecture exhibition catalog drafts7 hint at some of the struggles she had in making sense of the theme. Page after page discusses the pavilions of the 1925 exhibition, as if they were the Mother Stone for Deco architecture, but with little in the way of conclusion. Then, without connecting the dots or pausing for breath, she jumped the Atlantic to list the features of the 54 buildings and structures being included.

The pressing motivation was promotion of the historical merit of these buildings so that they might be preserved. This might be why they are described as “Art Deco” – in the catalog the term is frequently followed by “Style Moderne” in brackets – but who knew what that meant? “Art Deco” had a ready and hungry audience.

In the 1970s, New York was bankrupt and buildings from the ’20s and ’30s were reaching their commercial end of life. The fifty year old towers that did remain were in decay and being sold off piece by piece – the buildings were worth less than the sum of their parts. The catalog quotes William C. Shopsin, AIA Preservation Coordinator for New York.

“The cult of (Art) Deco has apparently become respectable once again and its incredible popularity has wreaked havoc with the scant number of fine [buildings] which managed somehow to survive. It is easier to find a buyer for decorative elements such as sconces, railings, panelling, plaster work and glass than for an interior or building preserved intact.”

Varian’s ploy may have worked. By linking the buildings in the public imagination to the chairs and trinkets they knew and loved, as “art deco”, people began to regard these disparate old buildings with fresh eyes. Preservationist eyes. The Chrysler building was inscribed by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1978, with the Empire State building following in 1980.

In choosing to paint New York’s towers as the direct continuation of the flimsy Parisian confections of 1925, some more robust precedents were left out. I’m going to look at just two of them.

Imperial Waiting Room, Helsinki Railway Station, sketch c.1909, Museum of Finnish Architecture. CC BY 4.0

Helsinki Railway Station, sketch – Estonian War Museum, Estonia – CC0.

It’s hard to look at images of Eliel Saarinen’s Helsinki Railway Station and not think it’s from the 1920s. Designed from about 1909 to 1911, the opulent colours, bold stepped geometries and simplified art nouveau motifs prefigure buildings designed two decades later. The station was completed in 1914 but not opened until 1919, after a world war, revolutions and civil war. Russian royalty never had a chance to wait in their room. Saarinen migrated to the U.S. in 1923, buoyed on by his second placing to John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood in the Chicago Tribune building competition.

Convocation tower, 1921. Architect: Bertram Goodhue. Illustrator: Hugh Ferris. CC0.

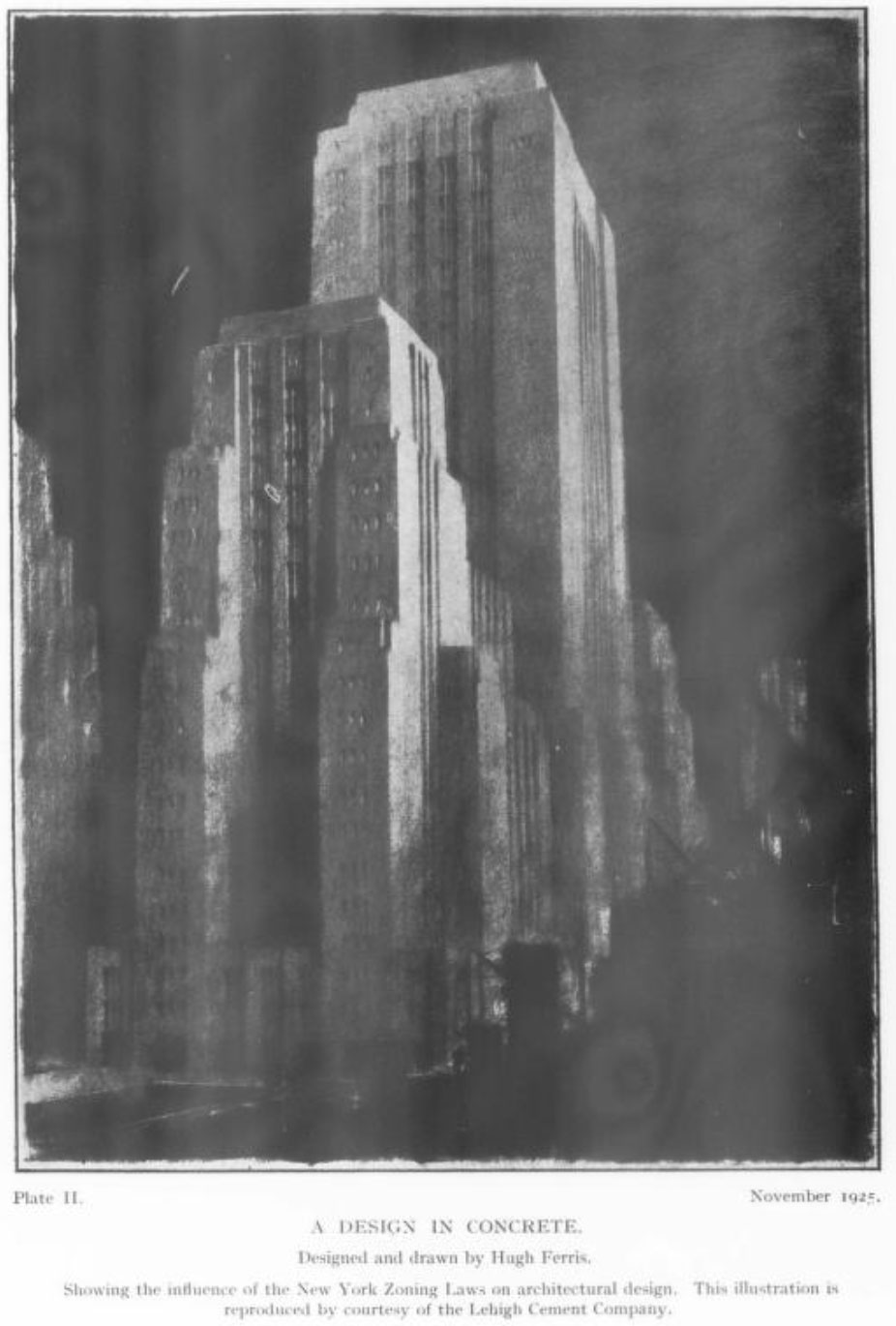

In the ’20s, finishes, steps and curves of the modern decorative arts were, when scaled up, found to be a pliable fit for New York’s 1916 Building Zone Resolution setback rules. Or rather, architects like Bertram Goodhue and Hugh Ferris grappled with the new rules and developed a complying aesthetic that was later subsumed into “deco”.

A 1925 feature on Ferris in the Architectural Record put it like this.

“The strange part of the business is that these laws, which had no concern whatever with esthetic have had a tremendous esthetic reaction, and for their complete and successful application the co operation of the artist-architect is now more necessary than that of the engineer-architect, for on his imaginativeness hinges henceforth not only the aspect, but the health, the comfort, the prosperity, indeed, the life of the city.”8

American Radiator Building, Flickr: Wally Gobetz CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Goodhue’s unbuilt 1921 scheme for the Convocation tower, moodily illustrated by Ferris, showed the gothic massing emerging from these exercises to reach to the skies. The tower was to house a large church at ground level, with a tower of offices above to break all height records (and pay the bills). It was one of several attempts in the early Twenties to claim the skyline back for religion, but mammon would triumph.

Hugh Ferris, November 1925.8

Raymond Hood designed the American Radiator Building in 1923 and it opened in the following year. It lays claim to being the first Deco building in the U.S., but Hood evaded attempts to associate it with anything. He did let on that reproductions of the work of Goodhue, Saarinen and others were scattered about the drawing tables for inspiration on how to deal with the skyscraper “problem”, and that the black and gold colour scheme was chosen to detract attention from the hundreds of darkened windows.9

“The Tribune and Radiator Buildings are both in the ‘vertical’ style or what is simply called ‘Gothic’ simply because I happened to make them so. If at the time of designing them I had been under the spell of Italian campaniles or Chinese pagodas, I suppose the resulting compositions would have been ‘horizontal’.”9

There was probably more going on than that. Hood designed the Radiator Building at peak Egyptomania, set off by the unearthing of Tutenkamen’s tomb in 1922 by Howard Carter and co. Public interest was commercialised, a quick and appropriative pillaging of ancient Egypt. Along with bobbed hair came the pairing of black and gold.

Art deco could provide the icing on the gothic cake. Finials and gargoyles were recast for a new secular client with geometries and eagles. Shiny tiles glistened in the sun and electric flood lighting made towers extend to the heavens at night. These towers were awe-inspiring attention-getters, which did no harm to the company whose name was above the doorway.

When the Radiator building became a New York Landmark site in November 1974, the committee including the following in its description.

The building was … dramatic at night when it was floodlighted. It became, in effect, an advertisement for the American Radiator Company. The vivid effects of coloration made it look like a giant glowing coal, even though Hood denied his intention of creating this conscious symbolic effect.10

I. Magnin building, Oakland, 1931. Image P. Johns 1993.

The 1970s framing of “art deco” architecture was an attempt to save what remained, and also opportunity to separate it in the popular imagination from European modernism – the less adorned forms of the International style. Deco architecture corralled all that was “modernistic” but too revivalist and eclectic to be in the Modernist camp.

The evolution of art deco continued into the 1930s and beyond. It would pull in new influences, take on new forms, and dot itself around the globe. If I can find the time, I might follow it forward.

1 “Return of retro: Mid-century, Art Deco homes fetch mega premiums as everything old is new again”, News Ltd, 9 May 2022. Link

2 Jérémie Cerman , « The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925 », Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe [online], ISSN 2677-6588, published on 22/06/20 , consulted on 13/04/2025. Permalink : https://ehne.fr/en/node/12305

3 The 1925 Paris exposition des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes and le pavillon de l’esprit nouveau: Le Corbusier’s Manifesto for modern man. Meet me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader. Lynn E. Palermo, ETC Press, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2014. p 241–247.

4 Art Deco Makes It – to the Museum, Newsday (Suffolk Edition), New York 26 Oct 1971, p 84.

5 After Art Nouveau, It’s Art Deco — Once Again, New York Times 20 Oct 1970, p 50.

6 The Best of Art Deco Architecture Displayed at Finch, Paul Goldberger, New York Times, 13 Nov 13 1974, p36.

8 Hugh Ferris and the Zoning Laws of New York, The Architectural Review 1925-11: Vol 58 Issue 348, p 174-177.

9 “Raymond Hood: Pragmatics and Poetics in the Waning of the Metropolitan Era”, R.A.M. Stern, in “Raymon Hood”, eds K. Frampton, S. Kolbowski, Rizzoli 1982, p 8-10.

10 Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 12, 1974

Posted by Peter on 28.04.25 in heritage

tags: 20th century, art deco, tall buildings